- Back to Home »

- Analysis , The Anatomy Of Visual Novels »

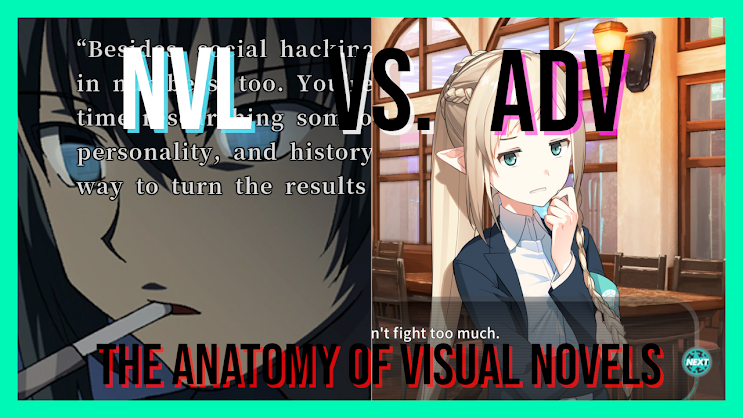

- NVL VS. ADV – An Anatomy of Visual Novels

Sunday, October 9, 2022

For

visual novels, the written word is their backbone and how it is

presented to the player is key to controlling their tone and pacing.

Over the years the methods of presentation have been standardised

into two types, ADV (ADVenture) and NVL (NoVeL). These two have

become the dominate styles and are often positioned as diametric

opposites in what they set out to achieve. When a developer creates a

visual novel they will often exclusively use one of these two types based on if it fits their intended vision. But what is it

that drives their choice and why have these two methods emerged as the

dominant forces in the medium? This article will examine these two

competing styles to find out what makes them tick and how you can utilise them

when making your own visual novel.

ADV

In

general ADV refers to a text box which only occupies as small section

of the screen. It is normally located at the bottom but also can take

different forms such as speech bubbles or other hovering text boxes.

ADV is by far the most popular type of text presentation with over

19000 tagged games in VNDB and it can be seen as the face of the

medium given how much it is associated with visual novels.

One

of the primary reasons for this popularity is the faster pace it offers. An ADV

textbox can only show a few lines of text at a time which the player

can quickly read before clicking to show the next

lines. This means the player is always being presented with new

content and encouraged to never dwell on previous lines which gives them a

sense that they are rapidly and constantly progressing through the

game. As such the overall pacing of the game is sped up and for games

focused on action or want a less dense feeling to their narratives,

the choice to use ADV makes sense. This can be further controlled to

the developer’s liking through the mixture of dialogue and

narration to slow or speed up the feeling of a scene. The 9-nine-

series is a good example of this practice with its mixture of slice

of life, suspense and action scenes demanding a shifting but brisk

pace. The game’s ADV delivers this by mixing speech heavy sections

with rapid descriptions of events depending on the needs of each

scene. Even with these elements it can be difficult to slow the

player down and make them contemplate what has occurred due to the

inherent forward momentum in of ADV and

the lack of space it gives to what has just happened.

Complementing

this faster pace is the lighter tone offered by unobstructed visuals.

The smaller textbox of ADV places a greater emphasis on the

backgrounds, portraits and CGs behind it and these cover the major of

what the player will be seeing. As you would expect this means

the visuals have to carry more of the weight in selling the narrative

and is a consideration for visual novels where their art style is a

big selling point as ADV allows it to shine. A focus on visuals also

creates a less serious tone than NVL due to the shorter segments of

text and an overall brighter feeling due to their prominence. This is the main reason slice of life and romance visual

novels prefer ADV as their aim is create an enjoyable but not

demanding experience for the player which they can comfortably slip

in and out of and ADV provides this flexibility to the developers.

One of the most prominent examples of this practice can be found in

any Yuzusoft game where the lighter tone of ADV is utilised to its

full effectiveness with their decorative and translucent text boxes

and bright aesthetic. It is impressive to see how small changes to

the colours of an interface can shift the player's

perceptions of a work towards a more relaxed atmosphere.

By

emphasising images through the smaller textbox of ADV, the styles

of narrative told using it tend towards an external focus. What

this means in practice is that these visual novels tend to have flat

or self-insert protagonists with the focus being placed on the

interactions between and other characters to carry the players

interest. Amnesia: Memories is an extreme example of this external

focus with its complete commitment to the self-insert protagonist and

reliance on conversations between characters to carry the narrative

weight. There is only a limited amount of introspection possible in a

format which is inherently forward moving and what

is present tends to be brief and supported by emotional moments with

members of the core cast. This is one of the major downsides of the

momentum offered by ADV, slowing things down can be difficult without

killing the pacing of the overall narrative.

Another

downside of ADV is lack of control it has over what text is shown on

screen at any one time. This is due to the limited space in the

textbox only allowing for a few lines to be displayed at once. As

such there is very little room for a game using ADV to experiment

with what and when things are shown on screen and the potential

effects this can have on a scene. The narrative presentation of this

type of game is simpler in general and tends towards a more balanced

approach rather than focus on the quality of the writing which is why it is more popular with new developers and those

with a more mixed skill set.

NVL

The

approach of NVL to text and narrative presentation is in many ways

the other extreme to the ADV method. It generally manifests as a

single large textbox covering most of the screen, sometimes with a

boarder around the edge, through which the visuals bellow can be seen

even if they are partially obscured.

When

a developer chooses to use NVL it is clear they want the writing to

be front and centre with the player's undivided attention. This is a

result of having the text take up a good portion of the screen and it

changes how the player interacts with the game. The presence

of more lines of text on screen at any one time creates a slower pace

to the narrative since past lines linger on the screen and the player

may reread them in light of the new information being presented to

them. We can see this clearly in Higurashi When They Cry which

utilises its tense and horror based narrative to make the player hang

on each sentence for a clue and attempt to find meaning in how the

lines are presented, which in turn fuels the atmosphere in a cyclical

manner. A side effect of this approach is the introduction of a more

demanding tone than is found in ADV due to the increased prominence

of the text and the way in asks you to dwell on the complete picture each

page is showing instead of just a since line. These combine to favour

more narratively complex stories since these elements of NVL are

often overkill for simpler tales.

One

of the largest benefits to using NVL is the minute level of control

it is possible gain over what text is shown as well as where and

when. This gives the developer the ability to emphasise key moments

by breaking from the established structure of the text and surprising

the player. These can be something as simple as a single word at the

centre of the screen to as complex as an entire scene presented as if

it were a text chat log. Perhaps the most vivid example of this is

Fate Stay Night which uses the colour, position, font and shapes

available to control player perceptions with a level of

finesse not possible without NVL. The ability to spice up the

narrative presentation can never be underestimated and it injects

life into what might otherwise be a boring wall of text. However,

there is the ever present risk of overusing this trick and the

temptation to show off through it must be controlled since it will

rapidly become familiar and breed complacency in the player.

The

focus of visual novels which use NVL tends towards the internal over the

external with the protagonist’s intimate thoughts being on display

for the player. Having text covering the screen naturally increases

the sense of familiarity the player has with its contents and by

extension the characters they portray. Linked to this is the needed

for an increased amount of words to cover the extra space provided by

NVL which often leads to the narrator character spilling their entire

train of thought at the slightest provocation. For example, Lonely

Yuri is almost exclusively introspection and despite it been a short

game it uses NVL to cover the screen with inner thoughts and

feelings to sell the mood of work. This is both a blessing and curse

as if handled well it can give the player a sense of the depth of each

character and empathise with them, but on the flip side it can lead to

narrative bloat which can kill the pacing of a scene.

A

major drawback of utilising NVL is way in which it pushes the visual

aspects of the game into the background. By placing a large text box

in front of both the background and portraits, it creates a sense of

distance from them and encourages the player to consider them less

important than the writing. As you would expect this means that their

art styles often tend towards clearer shapes and an uncluttered

visual presence since a more distinctive and loud use of colour and

form would become muddied or lost under the layer of text. While this

is normally worked into how the game presents itself so as to not

draw attention to it, there is undeniably something lost from not

being properly able to engage with the visual aspects in a more

chaotic and expressive fashion.

Merging The Two Sides

So

far I have been presenting ADV and NVL as if they are entirely

opposite and incompatible with each other. Of course this is not

true, in reality there is nothing stopping a developer from switching

between the two styles depending on the needs of the scene. Do you

want to have a moment of introspection then switch to NVL, or perhaps

you want a fast paced actions scene then switch to ADV. Wonderful

Everyday perfectly encapsulates this mixed philosophy as it weaves in

and out of both styles of presentation to allow the importance of a

scene or moment to be understood by the player. On top of all of this

it allows for the ability to play with player expectations through

establishing one of the styles as being only used for a certain

character or type of scene only pull back the curtain to reveal the

truth later on. The flexibility on offer is endless and can be

tweaked to fit the needs of the game’s narrative further adding

to the toolbox available.

If

utilising both styles opens so many possibilities, why is it not used

in every visual novel? The simple answer is most games do not need to

use it to achieve their desired story. Adding in an additional style

could create unintended confusion for the player because they might

lose track of what is going to due to the constant switching. On top

of this, the bouncing backwards and forwards between the two may lead to the

overall experience feeling unfocused. It takes a skilled hand to

navigate the correct use of this merger of styles and avoiding these

possible drawbacks by focusing on one style and its benefits is often the better choice.

Conclusion

As

with any medium there are differing approaches to presentation and none

of these are necessarily better than any other, but instead offer

benefits to certain genres and themes. Such is the case with the ADV

vs. NVL debate. On the one side we have ADV with its tendency towards

faster pacing and external focused narratives and on the other we

have NVL with its introspective tendencies and more demanding tone.

Of course you can combine the two in the same visual novel and play

with their contrasting properties if you are willing to run the risk

of confusing the player. Each one of these options is valid when used

properly and allow the developer to have control over the effects of

both the text and visuals in order to achieve their desired emotion

or theme. In the end you will have to make the call about what you

feel will work best within your visual novel and lean into what makes

your chosen style tick for the best results.